A Vaishnav himself, Karsandas showed how priests exploited women sexually. It led to the Maharaj Libel Case, the ‘greatest trial of modern times since the trial of Warren Hastings’.

Karsandas Mulji, a journalist, author, and social reformer, made significant contributions to society in mid-19th century Bombay and Gujarat. Within his brief 39-year lifespan, he founded several magazines and successfully defended himself in the famous Maharaj Libel Case of 1862 at the Supreme Court of Bombay.

Personal life

Born to a Gujarati Vaishnav family. He was raised by his mother’s aunt after he lost his mother when he was quite young. Karsandas attended Elphinstone college for his education and took part in Gnan Prasarak Mandal’s events. Karsandas started working as a journalist in 1851, when Dadabhai Naoraji created the Anglo-Gujarati Newspaper Rast Goftar. He was later repudiated by his family because of his views on widow remarriage. After a visit to England on business in connection with the cotton trade, which was not successful and brought on him excomunication from his caste because of the notion prevalent at those times regarding crossing the seas.

That year, Karsandas faced his first major challenge. He penned an essay for a literary competition, advocating for widow remarriage. When the news reached Karsandas’ elderly aunt, who had cared for him following his mother’s death, she promptly evicted him from her home. At the time, Karsandas was married. The young journalist then started supporting through a Claire (junior) Scholarship, which he earned after passing an examination, and securing employment at a charitable school founded by Sheth Gokaldas Tejpal.

Fight against exploitation

Undeterred by social and familial backlash, Karsandas continued to contribute to Rast Goftar. But he soon felt the need to do more. In 1855, with the support of wealthy reform-minded individuals, he launched his own magazine, Satyaprakash, which boldly confronted outdated traditions and societal problems. A Vaishnav himself, Karsandas began to expose the misdeeds of Vaishnav priests, including their exploitation of women devotees.

When Vaishnav priest Jivanlalji Maharaj was called as a witness by the Bombay High Court in a case initiated by Dayal Motiram in 1858, he refused to attend. Moreover, he sought an order from London to exempt Vaishnav priests from court appearances permanently. At home, he coerced Vaishnavite followers to agree to three conditions: No Vaishnav could write against the Maharaj; no Vaishnav could take him to court; and if anyone sued him, the followers would bear the cost of the case and ensure that the Maharaj did not have to appear in court. Karsandas criticised this coercive agreement in numerous articles in Satyaprakash, terming it gulamikhat (agreement of slavery). Despite their hostility toward Karsandas, fellow caste members couldn’t excommunicate him, fearing more backlash and another court case. When he started losing followers, Jivanlal Maharaj fled from Bombay.

In response to the growing sentiment against the priests, Jadunath Maharaj, a young and eloquent priest from Surat, travelled to Bombay to restore the sect’s influence. He feigned support for reform and even agreed to preside over a function honouring female students at a time when conservatives opposed female education. The situation changed when Narmad challenged Jadunath Maharaj to a public debate on whether or not the scriptures permit widow remarriage. The Maharaj cleverly shifted the debate to questioning the divine origin of the scriptures, leaving the discussion unresolved.

Famous Maharaj libel case of 1862

Narmad found a supporter in Karsandas, who challenged the Vaishnavite priests’ coercive and immoral practices. His article dated 21 September 1961 in Satyaprakash, titled Hinduono Asal Dharma ane Haalna Pakhandi Mato (The Primitive Religion of the Hindus and the Present Heterodox Opinions), delivered the heaviest blow, accusing them of engaging in sexual liaisons with female devotees, among many other charges. It further stated that the book of Gokulnath, the grandson of Vallabhacharya, who founded the Pushtimarg sect of Vaishnavism, endorsed immorality.

It led to the Maharaj filing the famous libel case in the Bombay court; it was called the “greatest trial of modern times since the trial of Warren Hastings”.

The Maharaj filed the lawsuit worth Rs 50,000 against Karsandas and the paper’s publisher, Nanabhai Ranina. Fearing he could be in trouble if any of his Bhatia disciples testified in court, the Maharaj convened the entire Bhatia community of Bombay and decreed that anyone who testified against him would be excommunicated. Upon learning about this meeting, Karsandas accused nine Bhatia leaders of conspiracy in the Bhatia Conspiracy Case — which was filed before the libel case proceedings had even started. Justice Joseph Arnould fined two leading Bhatias Rs 1,000 each and seven other defendants Rs 500 each. He also awarded Rs 1,000 to Karsandas as case costs, which were estimated at Rs 4,000 in total.

The libel case began on 25 January 1862 and attracted large crowds to the court. Despite immense pressure, Karsandas remained steadfast. Thirty-one witnesses for the plaintiff and thirty-three witnesses for the defendants were examined; Jadunath Maharaj was brought to court, which ultimately dismissed his defamation charges.

In his judgment delivered on 22 April 1862, Judge Arnould stated: “It is not a question of theology that has been before us! It is a question of morality. The principle for which the defendant and his witnesses have been contending is simply this: That what is morally wrong cannot be theologically right.” He commended Karsandas and his allies for their determined fight against a powerful and corrupt leader and for publicly denouncing and exposing evil practices. The court awarded Rs 11,500 to Karsandas, who had to bear a total expenditure of Rs 14,000 during the trial.

The case came to be a crucial precedent in establishing an important message that everyone, including priests, is equal under the law and “rejected the State’s traditional role as gaubhrhaman pratipa (Protectors of cows and Brahmins)” as noted by Achyit Yajnik and Makrand Mehta in their booklet titled Karsandas Mulji: Jeevan-nondh on the author. Karsandas co-founded Streebodh, a women’s magazine launched in 1857 and also published a weekly called Mumbainu Bajar (the Bombay Market) for some time. During his tenure as Assistant Superintendent of Rajkot state, he published a monthly journal titled Vignanvilas on science and industry. The author documented his travels to England in one of his books.

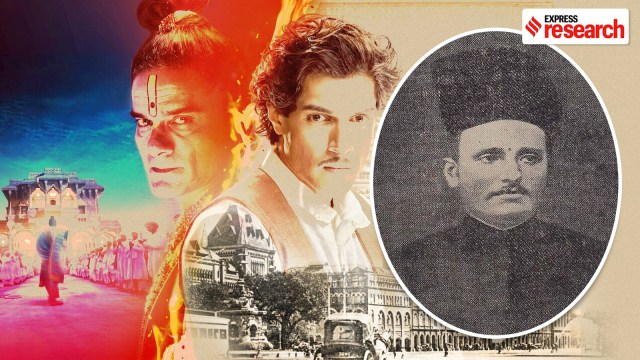

Karsandas, who died in 1871, is remembered mostly as the social reformer-journalist who won the Maharaj Libel Case. Bollywood superstar Aamir Khan’s son Junaid is set to make his debut in a film about the case. The film may revive the legacy of Karsandas’s battle against social-religious malpractices, which, today, lies buried only in Gujarati archives.

Netflix biopic Maharaj

Maharaj, a biopic on Karsandas Mulji, a journalist and a social reformer, is currently streaming on Netflix.

Mulji gained fame and notoriety after he accused a religious leader of sexual impropriety. In response, the accused, Jadunath Maharaj, filed a libel case against Mulji, which played out in dramatic fashion within the confines of the Bombay High Court in 1862. Like its protagonist, the producers of Maharaj were also called before the Gujarat High Court, when members of the Vaishnavite sect objected to the “scandalous and defamatory language” used in the film.